Britain

Britain has a long and distinguished history in many areas of human endeavor, but none is more impressive than their achievements in science. From the basic sciences in general, the names of Roger Bacon (1214-1294), Robert Boyle (1627-1691), Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727), John Dalton (1766-1844), Michael Faraday (1791-1867), and Lord Kelvin (1824-1907) rank among the greats of all time. It is no less the case in the fields of biology and medicine, where we will have much to say about people such as William Harvey (1578-1657), Stephen Hales (1677-1761), William (1718-1783) and John (1728-1793) Hunter, Edward Jenner (1749-1823), Sir William Hooker (1785-1865), Sir James Young Simpson (1811-1870), Charles Darwin (1809-1882), Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817-1912), Joseph Lord Lister (1827-1912), and many more.

The places associated with these men and women are inevitably scattered, and many more historical associations survive of some than of others. In recent British history, there have been two events in which great physical destruction took place. The first of these was their Civil War in the first half of the seventeenth century, and the second was in World War II (1939-1945). Regrettably, the history of biology and medicine did not escape these two disasters, and in addition, time and change have taken their toll. We must also note that it is only in very recent times that it was even thought desirable to preserve scientific monuments. Nevertheless, Britain is very richly endowed with such monuments.

Roads in Britain are generally good, and British Rail offers excellent service to most places. There are also many bus services. All road directions we give are from London, unless otherwise noted.

ALDERSHOT (Hampshire)

Location-35 miles southwest of London

Train-From London (Waterloo)

Road-Take the M3 or A30 towards Basingstoke. Near Camberley, turn off along the A321 to Aldershot.

Aldershot is the “military town” of England, where soldiers have been trained for over a century. However, there are also three excellent historical museums: dental, medical and nursing.

Royal Army Dental Corps Museum

H.Q. and Training Centre

Royal Army Dental Corps

Queens Avenue

Aldershot.

Phone: (0252)-24431 and ask for the Royal Army Dental Corps Training Center

Opening hours: Upon request at the main desk of the training center. No charge for admission.

Fortunately, the founders of this museum concentrated on dental history rather than military history, and the layout of the museum is chronological starting about 1660 and continuing to the present day. The whole museum is a remarkable documentary display of the advance of dentistry for over 300 years. Some of it is pretty grim! In addition to the various, and very interesting instruments, apparatus, etc., the visitor is reminded of the many problems and events which have affected dentistry directly and indirectly. For example, as early as the 17th century, military surgeons were required to preserve the soldiers’ front teeth so that they could bite through the cartridge when loading their flintlock muskets. With the advance of weaponry, and biting through the cartridge no longer necessary, the surgeon specialized in the preservation of the molars so that the soldiers could chew their food properly, and the front teeth were no longer considered essential! Vivid displays depict jaw and facial wounds so common in war (particularly in WW I with its trench warfare), and these involved the dentist in their repair. Quite contrary to popular belief, some remarkable “plastic surgery” was done in WW I, rather than having to wait for WW II, and much of this was done by surgeons and dentists working together. The leader in this area was the New Zealander, Sir Harold Delf Gillies (1882-1960). Of great interest also is a comparison of field dental units of WW II from British, American and German armies. One is struck at once by the enormous technical superiority of the German unit. In our opinion, this museum is a “little gem”.

Royal Army Medical Corps Historical Museum

Keogh Barracks

Ash Vale

Near Aldershot.

Phone: (0252)-24431, Ext. Keogh 212

Opening hours: Monday-Friday: 9.00-16.00

Weekends-By appointment.

No charge for admission.

One of the earliest recorded references to army medical doctors is found in the Greek poet Homer’s account of the siege of Troy (1190 BC), and certainly from that time onwards almost all armies have supplied some kind of medical care for their soldiers. This museum displays the development of that care, and consequently, is of great interest for the history of medicine in general.

The museum is relatively new, having been opened in 1981, but it is based on a much older one. Fortunately, it is being kept up to date under the able leadership of Lt. Colonel Roy Eyelons, who is the curator (1986), and there are even plans for expansion.

The displays are a blend of medical and military history, and are arranged chronologically in ten sections. The first section is from the earliest times to 1660, and the last from 1945 to the present. Some of the displays are very realistic and there is no attempt to hide the horrors of war, but great emphasis is placed on what the medical services can do to alleviate suffering. Some of the more spectacular items on view include the following: Hanoverian Army medical instruments from 1715, Napoleon’s dental instruments, water color drawings of the wounded at Waterloo (1815), a bullet extractor using electricity for detection, branding instruments used on deserters, iron lungs, mobile field anesthesia apparatus and a mobile surgery table with a mock casualty. All in all, an important museum in the history of medicine, and a good place to learn the important contributions made to medicine under the pressures of war.

Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps

Training Center

Nursing Museum

Farnborough Road

Aldershot.

Phone: (0252)-24431, Ext. 315 or 301

Opening hours: By appointment only, and it is necessary to phone in advance.

No charge for admission.

Within this training center for army nurses is a small museum devoted to the history of army nursing, and in fact, it supplies a history of nursing in general. A small pamphlet, as a guide, is available, and an excellent history of Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps may be bought, and we recommend this.

This museum is a blend of military and nursing history, and tends to be photographic except for the displays of nurses’ uniforms. However, they have various artifacts of the nursing profession and some priceless objects such as the carriage used by Florence Nightingale (see under East Wellow, Middle Claydon and London, St. Thomas’ Hospital) in the Crimea. The displays are arranged chronologically, and at present, the museum is being redesigned and will, in due course, exhibit many new items from their un-displayed collections. This is the only Nursing Museum we are aware of, and is well worth a visit.

Before leaving Aldershot, the visitor will no doubt wish to see many other things there of historical interest. These are explained in a pamphlet entitled “Aldershot Military Town Trail”, which contains directions for seeing such diverse items as a Dakota preserved from WWII and a military horse cemetery!

ARDINGLY (Sussex)

Location – 35 miles South of London

Train – From London (Victoria) to Haywards Heath, and then by bus or taxi to Ardingly.

Road – Take the A23 going south from central London and join the M23 towards Brighton. Just past Crawley join the A23 again as far as Handcross. Then turn left (east) onto B2110 towards Balcombe, and follow this across the reservoir. At Ardingly turn left (north) onto B2028 to Wakehurst Place Gardens.

Wakehurst Place Gardens

Ardingly.

Opening hours:

Summer daily 10.00-19.00

Winter daily 10.00-16.00

Small charge for admission.

Wakehurst Place is a National Trust property leased to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food as an addition to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew (see under Kew). This supplies Kew with a much greater variety of growing conditions for various plants, and much larger facilities for botanic research. The gardens consist of 462 acres, most of which is natural woodland, in which the visitor can roam freely. This is an ideal place to see various species of trees, shrubs, etc., and their ecology in the natural woodlands of the area. Also there are extensive formal gardens, where there are large numbers of imported species – – all beautifully maintained.

It is here at Wakehurst that the Royal Botanic Gardens perform all their plant physiological research. They are particularly concerned with the physiology of seeds, seed germination and storage. They maintain a seed bank for many different types of people, including conservationists. They are concerned to find out how long various seeds can be stored and still remain viable. There is enormous variation between species, but most can probably be stored from 50-100 years.

Inscribed on the sundial within the gardens are the following lines by the American poet John Whittier (1807-1892), which expresses the attitude of those who love plants:

Give fools their gold and knaves their power

Let fortune’s bubbles rise and fall

Who sows a field, or trains a flower

Or plants a tree, is more than all.

Although the primary function of Wakehurst Place is scientific botany, it is also a very beautiful place and should not be missed.

ASHFORD (Kent)

Location-50 miles southeast of London.

Train-From London (Charing Cross)

Road-Take the A20 to the south, and follow this (or the M20) through Maldstone to Ashford.

Ashford, Kent, is not known to have been directly associated with William Harvey (see also under Folkestone, Canterbury and Hempsted), the man who discovered and proved the phenomenon of blood circulation. But the country of Kent is “Harvey Country”, so to speak, for it was here that he was born and brought up, and there are two things in Ashford which commemorate the memory of this giant of medicine.

Willesborough is a suburb of Ashford, which has a nice pub called “The William Harvey”. However, more important is the fact that in the garden of the pub, there is a fine statue of William Harvey. It has an interesting history. About 160 years ago it was sculptured by Henry Weekes, and stood outside the Royal College of Physicians in London. During WWII, the college was badly bombed and the statue damaged. While the debris was being cleaned up, and in some way, no one knows how, the statue found its way to the garden of this pub where it is today! It is well looked after and interesting to see. Also in Willesborough is the new William Harvey Hospital and outside the main entrance is a copy of the William Harvey statue at Folkestone. It is very impressive.

BERKELEY (Gloucestershire)

Location-105 miles west of London and 12 miles south of Gloucester.

Train-From London (Paddington) to Gloucester, and then by bus or taxi to Berkeley.

Road-Take the M4 to the west as far as exit 20 (which is where it crosses the M5). Take the M5 north to exit 14 and then join the A38 north to Stone. At Stone, take the B4509 (left) to Berkeley.

Berkeley (pronounced Barkeley) will remain celebrated for all time as the birthplace and home of one of mankind’s greatest benefactors, Edward Jenner (1749-1823), whose monumental work first brought under control the dread disease of smallpox, and which it would not appear has been eradicated from the earth- – we may hope forever.

The Jenner Museum

The Chantry

Church Lane

Berkeley, Gloucestershire

Phone: (0453)-810631

Opening hours: April 1-September 30, every day, 11.00-17.30

October-Sundays only, 11.00-17.30

Closed November-March

Small charge for admission.

In a world now devoid of this disease, it is really very difficult for us to understand the terrible scourge of smallpox. It was highly contagious, and many a doctor contracted it while trying to treat a patient. It killed thousands (particularly children) and left other thousands visibly and badly scarred for life. The disease was probably of eastern origin and was brought to Europe by returning crusaders in the 11th and 12th centuries. From there, in due course, it spread throughout the world. It was a major factor in the virtual extermination of the North American Indian.

Edward Jenner was born in Berkeley, where his father was vicar, but at the age of five, both his mother and father died leaving him an orphan under the care of his elder brother Stephen, another clergyman. At the early age of twelve, Edward was apprenticed to a surgeon, David Ludlow, under whom he worked for nine years. Then at the age of twenty-one, he went to London to study anatomy and surgery under the most famous doctor of his day, John Hunter (see under London and East Kilbride) with whom he corresponded until the latter’s death in 1793. In 1773, Jenner returned to Berkeley, established himself in medical practice there, and in due course, married Catherine Kingscote. Upon marriage, they moved into Chantry Cottage, where they lived (with only short absences) for the rest of their lives.

Jenner, following the accepted practice of his day, inoculated many of his patients against smallpox (using fluid from a smallpox pustule) but soon found that some patients were resistant to the disease, and learned further that these patients had apparently all had a disease contracted from cows, known as cowpox. This is a relatively rare and mild disease, though prevalent in Western England at the time, and Jenner found that amongst milkmaids and others having close contact with cows, it is generally believed that contraction of cowpox gave protection, if not complete immunity, against smallpox. Thus it occurred to Jenner that if patients were inoculated with the fluid of a pustule of cowpox, from which they would contract cowpox (hopefully in mild form), that this might confer immunity to smallpox. Furthermore, and most important, Jenner hoped to create a reservoir of cowpox by transferring the disease via inoculation from human to human. This indeed proved possible, and it also proved possible to artificially store and ship the fluid obtained from a pustule of cowpox.

Jenner was reluctant to try the crucial experiment, but finally on May 14, 1796 (perhaps remembering the famous advice of his former teacher, John Hunter, “But why think? Why not try the experiment?”), Jenner inoculated an eight year old boy, James Phipps, with the fluid from a cowpox pustule obtained from a milkmaid who had the disease. James contracted cowpox, but recovered within a few days. Then on July 1, the same year, Jenner inoculated him with smallpox and to everyone’s delight, the boy did not contract smallpox.

Jenner understood the importance and potential of his discovery, and in the following year, 1797, he sent a short paper on the subject to the President (Sir Joseph Banks) of the Royal Society. His paper was rejected! However, in 1798, he published, at his own expense, a short book describing the nature of cowpox and the immunity (not permanent) it confers against smallpox. The book was entitled: “An inquiry into the Causes and Effects of Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the Western Counties of Cowpox”. It was the result of enormous perseverance and careful reasoning, and is one of the great works in medical history. With its publication, Jenner may be considered the founder of immunology with all the blessings which since have followed from it. He also coined the word virus (Latin=poison or slimy liquid). The process of inoculation with cowpox quickly became known as vaccination (Latin: vacca=cow), and soon spread far and wide.

Mary, Countess of Berkeley (1767-1844), a very influential local woman, persuaded Jenner to vaccinate her large family of children, and through her, Jenner also vaccinated the royal children of George III. This helped enormously to spread and popularize vaccination. By 1801, it was being used extensively in the Persian Gulf and India, and Jenner personally sent vaccine to President Thomas Jefferson of the United States, who vaccinated his family and friends at Monticello.

Fame, honors, but little fortune were poured upon Edward Jenner after his discovery. Yet it is nice to record that despite this, he remained a simple country doctor in his native Berkeley. The British Parliament voted him a grant of money, which made life easier for him, and in 1804, although Britain and France were at war, Napoleon Bonaparte had a medal struck in his honor, and in 1805, made vaccination compulsory in the French Army. Also at Jenner’s personal request, Napoleon released some British prisoners, and in so doing is said to have remarked: “We can refuse nothing to that man”. Such was Jenner’s prestige.

Jenner’s wife, Catherine, died in 1815, and he later died of a stroke in 1823. Despite the fact that he could have been buried in Westminster Abby, he preferred Berkeley Church where his body lies today.

The Chantry (formerly Edward Jenner’s house) was bought by the Jenner Trust and the British Society of Immunology, and opened as the Jenner Museum in May 1985. There was previously a small museum in a little house on Church Lane.

The rooms comprising the museum are as follows:

1. Entrance Hall, with various items for sale and pictures depicting various events in Jenner’s life.

2. The Jenner Room, with cases of articles belonging to Jenner, including some of his instruments, manuscripts, photographs, paintings, prints, publications, family letters and his original handwritten will of 34 pages.

3. The Smallpox Vaccination Room, with pictures of people with cowpox and smallpox, cases of instruments used in vaccination, and cases of honors bestowed on Jenner.

4. The Study. Jenner’s original study, with his furniture, instruments, books, etc., all beautifully restored and displayed behind glass.

5. The WHO room. The World Health Organization Room, with displays depicting the work of WHO.

6. The Immunology Room, showing the history of immunology from a historical perspective.

7. There are also administrative offices and a conference room

Adjacent to the Chantry is the Jenner Hut or Temple of Vaccinia, where Jenner vaccinated the poor from far and wide, and also the village church where he and his immediate family are buried. His grave is near the altar. Jenner was born in what is now the town post office.

No visitor to Berkeley will want to miss Berkeley Castle, which adjoins the churchyard on the outskirts of the town. This is the private residence of the Berkeley family, but is periodically open to the public by the Berkeley’s permission. Incidentally, the Berkeley family goes back 800 years in a direct male line! Of great interest, also is that the Berkeley family has always been concerned with the support of potentially great men and their achievements, for not only did they sponsor Edward Jenner, but William Harvey as well. Of further interest is the fact that it was a member of the Berkeley family who gave his library to start the now famous University of California at Berkeley.

In addition to all these interesting things to see at Berkeley, we would recommend that visitors also take the opportunity to see the magnificent Jenner statue in Gloucester Cathedral, and the nearby and fascinating Wildfowl Trust at Slimbridge.

BROADSTONE (Dorset)

Location – 110 miles southwest of London, near Bournemouth.

Train – From London (Waterloo) to Bournemouth, then by taxi to Broadstone.

Road – From London take the M3 or the A30 to beyond

Basingstoke, and fork onto the A33 to Winchester. Follow the A33 around Winchester and then fork on to the M27 towards Cadnam. At Cadnam join the A31 to Ringwood and Wimborne Minster. At Wimborne Minster take the A349 towards Poole, but before reaching Poole take the small marked road to Broadstone.

Broadstone Cemetary is the final resting place of the great biologist and explorer Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913). Wallace died in a house he owned nearby, but it has now been completely demolished.

Alfred Russel Wallace was born in Usk, Monmouthshire, on the north side of the Severn in Wales. (The house in which he was born still stands, but it is privately occupied.) His family suffered periodic economic setbacks, but he appears to have had a happy childhood though a minimum of formal schooling. Wallace is an excellent example of a self-educated man. He never attended university, but by wide reading from the earliest age onwards he became a very knowledgeable person. For several years he worked with his brother, William, as a surveyor, but in 1848, at the age of 25, he set out on the first of his many travels to far away lands. From 1848-1852, he explored the Amazon basin, and collected and studied prodigious amounts of natural material which he took with him on the return voyage to England. However, disaster overtook the ship on which he was traveling. It caught fire and sank, and Wallace barely escaped with his life. All of his specimens were lost. Despite this, in the following year, 1853, he published his fascinating book “A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro.” The evidence is clear that from this time, perhaps before, Wallace was interested in organic evolution, and the mechanism of “speciation.” In 1854 Wallace set out for the Malay Archipelago, and for the next 8 years he explored and collected in the general region of what is now known as Indonesia. One of his specific aims was to study the geographical distribution of animals, with the hope of uncovering their evolutionary origins. He was eminently successful in his quest! In 1858, while Charles Darwin (see under Downe) was at work on his book, which was eventually to become “The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection,” Wallace wrote to Darwin and Wallace, and thus Wallace may rightly be described as the co-discoverer of evolution by natural selection. However, it was left to Darwin to put the theory forth in understandable terms, to document it with his overwhelming amount of evidence, and to explain its scientific implications. In 1862, Wallace returned to England, hailed as a great naturalist, and rightly so. In 1869 his experiences in Malay were put forth in his book “The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-Utan, and the Bird of Paradise. A Narrative of Travel with Studies of Man and Nature.” It is one of the best natural history books ever written. More important still, from a scientific point of view, was his work. “The Geographical Distribution of Animals” (1876). With this he founded the science of animal geography and it is still read by professional students of the subject today. It explains the mechanisms, on a worldwide basis, by which animals have evolved in their present habitats. Wallace wrote a great deal more in his long life of 90 years, and in some of these his curious religious views are intermingles with his scientific though. But it is for those works already mentioned, and his great theory of evolution by natural selection, that he will be remembered as a evolution by natural selection, that he will be remembered as a naturalist and scientist of the highest rank.

To find Wallace’s grave in Broadstone Cemetary, enter by the main gate and follow down the walkway. Less than 100 yards on the right, and near the walkway, you will see a large simulated tree trunk on top of his grave. He and his wife, Annie, are buried side by side here, and there are two simples’ plaques on the tomb giving their names, birth and death dates. It is a pleasant thought that the great, and widely traveled naturalist lies in such a beautiful place.

CAMBRIDGE (Cambridgeshire)

Location-55 miles north of London.

Train-From London (Liverpool Street)

Road-Take the A11 which leads into the M11 at Wanstead. Follow the M11 until it again joins the A11 until just beyond Great Chesterford, then take the left fork onto the A130, which leads via A10 into Cambridge.

The history of Cambridge goes back to Roman times, when there was a Roman camp. However, when the Domesday Book was compiled 1000 years later in 1086 AD, there were still only 400 houses in Cambridge. Today, its frame rests on its university, one of the truly great educational centers of the world. It is younger than Oxford, and it is probable that its history is a “community of scholars” goes back to 1209, when some scholars from Oxford settled there after being forced to leave Oxford because of “trouble with the townspeople”! But by the middle of the century, it could rightly claim to be a university. In 1284 the university’s first college, Peterhouse, was founded, and many more have been founded over the centuries. At present, there are 31 different colleges.

The university is basically a federal structure, in which the colleges are semi-autonomous, and all students must belong to a college. However, it is the university which imposes minimum entrance requirements, is responsible for formal instruction, conducts examinations, and confers degrees.

Cambridge is an exciting, dynamic, and very pleasant place, and for “first-time” visitors, we cannot recommend too strongly that as soon as possible they visit the Tourist Information Center. It is in Wheeler Street, an extension of Benet Street, which in turn runs off King’s Parade. It is open Monday-Friday, 9.30-17.30, Saturdays 9.00-17.00, closed Sundays. Not only is the Information Center a mine of information on all things the visitor needs, but in addition it conducts guided “Walking Tours of the Colleges”. These are normally at 11.00 and 14.00, Monday-Saturday, and last about 1 ½ hours. They are popular and limited to 20 persons each. Thus it is best to buy your ticket well in advance if possible. This tour will give you a marvelous introduction and orientation to Cambridge and its university. One of the many nice things about Cambridge is that it is still small enough and concentrated enough, that virtually everything the visitor may want to see can be reached on foot, and that is certainly the way to see it. The main life of the city is on either side of the central street of St. Johns- -Trinity- -King’s Parade- -Trumpington.

In contrast to Oxford University, Cambridge has always encouraged the sciences, and has produced such men as William Harvey, Sir Isaac Newton, Stephen Hales, Charles Darwin and Francis Crick, all of whom had an enormous impact on the development of biology and medicine. Within the various colleges, laboratories, museums, etc., science has flourished, and the visitor to Cambridge can see some of the places associated with the great development of biology which has taken place there. We must stress, however, that Cambridge University and its colleges are active educational and research institutions, and the visitor should respect this fact and not expect to be able to see everything on demand. The porters’ offices at the entrance to colleges, are however, generally cooperative, and will tell you what is open to the public and what is not.

Gonville and Caius College

Trinity Street

It was here that William Harvey was a student between 1593-1599. His life,

discoveries and work are described under Folkestone. It is regrettable, however, that virtually nothing survives at the college that is known to have been associated with Harvey. It is not even known which rooms he occupied, but nevertheless, it is exciting to realize that Harvey once walked the courtyards and corridors to this college. There is a so- called “Harvey Court”, but it is modern and simply named in Harvey’s honor. Of particular

interest is their magnificent historical library with a fine collection of 16th and 17th century medical works from Padua, and there is little doubt that Harvey was aware of these, which in due course, led him to study at Padua, then the foremost medical school in the world.

The college library is not open to the public, but one may request to see it.

Trinity College

Trinity Street

This was the college of Sir Isaac Newton who was a student here between 1661- 1665. However, he stayed on at Cambridge as a professor until 1701. Newton was of course not principally famous for biological discoveries, but his work in physics and mathematics was so great that it influenced all science, and it would be inappropriate to ignore him while we were describing historical scientific associations in Cambridge. The rooms that Newton occupied, while at Trinity College, are known. They are at ground level and the exterior aspect is usually pointed out by the guide in one of the “Walking Tours of the Colleges”. Of further interest is the fact that in the entrance hall of the Trinity College Chapel (usually open), there is a magnificent statue of Newton as a young man.

Corpus Christi College

Trumpington Street

This is where Stephen Hales was a student. He is often referred to as the founder of plant physiology. His work is described under Teddington. Stephen Hales’ days as a student at Corpus Christi were from 1696-1700, but like Newton he stayed on at Cambridge, in his case until 1709. The only part of the College that survives from Hales’ days in the Old Court, which dates from 1350. The rest of the college is later than the 17th century. Stephen Hales unquestionably occupied rooms somewhere around the Old Court, but it is not known which ones. The Old Court can be found through an arch way to the left of the present Main Court. For those with more than passing interest in Stephen Hales, it is possible to purchase (for £1) at the college office, an excellent biography of him by the late Dr. A.E. Clark-Kennedy.

Christi’s College

St. Andrews Street

This was the college of Charles Darwin. His life and work are described under Downe. Darwin was a student at Christ’s from 1827-1831, and his major field of study was theology. However, it was during his days here that his biological interests were established, mainly due to the influence of Professor John Stevens Henslow (1796-1861), a very distinguished botanist, with whom he became a close friend. They are off the main quad to the right, up a small flight of stairs, and they are referred to as G4. One may see the location, but the rooms are privately occupied. In the main dining room, which can usually be seen if not in actual use, is a magnificent portrait of Darwin by W.W. Ouless, alongside other portraits of Christ’s importance also at Christ’s is their superb historical library, which is the same library Darwin knew and used. They have, among other things, over 100 letters, written by Darwin, while he was a student at Christ’s. The library is not open to the public, but permission to see it can be requested.

Darwin College

Silver Street

This college is of recent origin and is located in a lovely old house which belonged to one of the sons of Charles Darwin. Of great interest is the fact that it was here that Gwen Raverat (née Darwin, and Charles’ granddaughter) was brought up, and it was the setting for her classic work “Period Piece”.

Department of Zoology and Museum

Pembroke Street

Opening hours: Monday-Friday only, 14. 15-16.45.

Children must be accompanied by an adult.

No charge for admission.

The department has had a long and distinguished history in the development of modern zoology. It is a research and teaching department, but they have a very fine Museum of Zoology as well. It is not intended as a Natural History Museum. All the main groups of animals are arranged systematically, and it emphasizes taxonomy, anatomy and ecology. It Is very modern, and the exhibits superbly displayed. The curator is Mr. R.D. Norman, and if he is not busy (unlikely!), you may ask to see same of their very special

collections, which include fish and birds (including some Galapagos Finches) collected by Charles Darwin. They also have slides of the appendages of Darwin’s famous collection of barnacles, which he used as the basic material for these two volumes on living barnacles, and two on fossil barnacles. The zoological museum is a fascinating place for those with an interest in biology and its history.

The Botany Department

Downing Street.

Opening hours: Normal academic hours.

No charge for admission.

Historically this may be described as one of the homes of modern botany, for it is here for over two hundred years that botany has been pursued as a science rather than simply as an aid to medicine or as horticulture. This is an active department of teaching and research, but the visitor may ask to see their superb botanic library, and above all, their unique herbarium. Within this herbarium are the Galapagos plant specimens collected 150 years ago by Charles Darwin himself, and which played such a large role in helping him to unravel his theories on evolution. The “line of descent”, so to speak, for this collection was from Darwin to Professor John Henslow, to Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker to the Botany Department. Amazingly enough the collection is still not yet fully studied and documented. Within the library are some very fine busts of famous botanists which the visitor can see.

The Old Cavendish Laboratory

Free School Lane

It was here between 1951 and 1953 that Francis Crick and James Watson unraveled the structure of deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA), the basic material of life, and this was certainly the most important biological discovery of this century. In addition to Crick and Watson, Ernest Rutherford, J. J. Thomson and James Clerk Maxwell all worked within the walls of the Old Cavendish Laboratory. Crick and Watson actually worked in the Austin

Wing (clearly marked), and on the wall outside the main entrance is a plaque

commemorating the distinguished scientific history of the institute. Of interest also is the little house where Francis Crick lived while working on the structure of DNA. It is at 19- 20 Portugal Place, and has a “golden helix” hung above the front door! It is a private residence but visitors can see the outside. Francis Crick was born in Northampton in 1916 of middle class business-minded parents, and he was the only member of the family to exhibit an interest and indeed passion for science. In due course (1937) he received a B.SC. Degree in physics from University College, London, and afterwards worked as a research student until the coming of World War II in 1939 when he became a physicist with the British Admiralty. It was here in the Mine Design Department that he demonstrated his ability to go straight to the central core of a particular problem. However, it was not until 1947 that he went to Cambridge and turned his attention to biology, as distinct from physics. He joined the Cavendish Laboratory and was admitted as a Ph.D. student, in 1949, working on x-ray diffraction of protein. Here in 1951 he became associated with a young visiting American biologist, James Watson, and together for two years they worked “on and off” on the structure of DNA. They were successful beyond their wildest dreams. James Dewey Watson’s career, up to this time, had been less spectacular than Crick’s, but he was regarded as a very able young biologist. Born in Chicago in 1928, he received, in due course, his B.S. from the University of Chicago, and his Ph.D. from the University of Indiana, and at the time he met and worked with Crick as a “visiting fellow” in various places in Europe.

On April 25, 1953, Crick and Watson published the British journal Nature, their classic one page article “Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids”. In it they gave a diagram of what has become famous as the “double helix”, and in addition made a superb understatement, “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material”. Their theoretical structure and postulation proved to be correct, and with it a new era of genetic and molecular research, with all its implications, was ushered in. In 1962, Crick and Watson were awarded the Nobel Prize for their work, but it is important to point out that their achievements did not occur “in vacuo”, for the Nobel Prize also went to Maurice Wilkins, John Kendrew and Max Perutz, all of Whom contributed to this discovery. Many people have regretted that the prize was not also awarded to their co-worker, Rosalind Franklin, who died so tragically soon after this great event. Francis Crick and James Watson have both gone on to distinguished biological careers.

The Whipple Museum of the History of Science

Free School Lane

Opening hours: Monday-Friday 14.00-16.00

No charge for admission.

This is part of the University’s Department of the History and Philosophy of Science. Here in this museum are superb historical collections of microscopes, telescopes, mathematical instruments and apparatus of great variety, much of it used directly in medicine. There is also a library devoted to the history of science.

The University Botanic Garden

Bateman Street

Opening Hours: Monday-Saturday 8.00-17.00

No charge for admission.

This botanic garden is under the direction of the botany department. Its main functions are research and education, as has been the case since its inception, but it is a very beautiful place as well, and a haven of peace and quiet- -reinforced by the signs which read “no dogs, no games, no bicycles, no transistors”! Founded in 1760, it moved to its present site of 40 acres in 1831 . At this time Professor John Stevens Henslow (see previously) was Professor of Botany. He was a very dynamic and farsighted young man, and set the tone for the whole development of the garden, which still goes on today. The research function of the garden has tended to concentrate on taxonomy, but much plant genetic work has also been done there, included that of Sir William Bateson. In recent years the research function has increased, and they also train very high quality horticulturalists. In addition to the many special gardens and glass houses, there is a systematic garden with over 80 families of plants represented, and the trees surrounding the outer edge of the eastern half are planted in taxonomic groupings. A systematic garden is one in which the plants are placed and grown in their natural and evolutionary relationships. Being primarily a research botanic garden, it naturally has an extensive library which is particularly strong in the history of horticulture of the 17th and 18th centuries. There are also many unique and valuable general holdings going back to pre- Linnean times. There is also an extensive collection of botanical serials, monographs, maps, etc., some extinct journals and very interesting floras. All in all, the University Botanic Garden is one of the best and most distinguished in the world, and continues to play a large role in the development of scientific botany.

The Cambridge University Main Library

West Road

Opening hours: Not open to the public except by special permission, but from Monday- Friday at 15.00, the public can be shown around the library.

This is a vast modern complex dating from 1934. It was designed by the architect Sir Gilbert Scott. However, the origins of the University Library go back to the 14th century, and it was well established by the beginning of the 15th century. Since then it has had a checkered history, but today is certainly one of the great libraries of the world, and is particularly strong in the natural sciences. It is one of five copyright libraries in Britain, and as such, is entitled to a free copy of every book published in Britain. Its historical collections in the natural sciences are probably unrivaled anywhere. A very interesting historical sketch booklet of the library is available, and for lovers of biology, there is also published a “Handlist of Darwin Papers” in the possession of the library. The university library is the main depository for the Darwinian papers and books. Some of these are at times on special display, but normally are not available to the public except by special permission for scholarly purposes. The Cambridge University Library played, and continues to play, a huge role in the ongoing development of the science of biology.

Fitzwilliam Museum

Trumpington Street

Opening hours: Tuesday-Saturday 10.00-17.00

Sunday 14. 15-17.00

Closed Monday.

Small charge for admission.

In addition to the foregoing places of biological interest, no visitor to Cambridge will want to miss the Fitzwilliam Museum. Unfortunately, this marvelous museum is having such financial troubles that they have had to close some of the galleries on alternate days- -very distressing for the short term visitor. This is not a museum of science, but a great art and antiquities museum.

CANTERBURY (Kent)

Location-SS miles southeast of London

Train-From London (Victoria) direct.

Road-Pick up the A2 at Greenwich and follow this southeast through Rochester,

Gillingham, Sittingborne and on to Canterbury.

Canterbury, Kent, is famous for its Cathedral, and the fact that it is considered “the home” of Protestant religions. However, Canterbury has another claim to fame, namely that William Harvey (see also under Ashford, Folkestone and Hempstead) attended the King’s School as a young student. The King’s School adjoins the Cathedral and is closely associated with it.

King’s School

Canterbury

The King’s School is a choir school, whose origins are lost in antiquity but certainly go back well over 1000 years. The main entrance to the school is through the 13th century gate off Broad Street, which leads into the Green Court, and the buildings of the school surround this. There are many other walking entrances, including some from the gardens of the Cathedral. There is even an older entrance gate dating from the 11th century, but it is now bricked over, though still easily seen.

In 1588, at the age of 10, Harvey entered the King’s School, and remained there for 5 years. He was not a King’s scholar, but a day pupil, and probably lived in Hawks Lane, which still survives, though the actual house he lived in is not known. All the memorabilia associated with Harvey which the school possessed have been scattered since Harvey was there. However, it is a fascinating place to visit and realize that William Harvey studied and walked in these same building and grounds four centuries ago. He is by far their most distinguished pupil! Of course, the visitor to King’s School will also wish to see the adjoining Cathedral, which is the seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury and has a very long and interesting history.

DOWNE (Kent)

Location – 15 miles south of London

Train – From London (Victoria) to Bromley South, then by taxi or bus #146 (infrequent) to the village of Downe.

Road – From Londo, take the A21 south at Lewisham and follow this through Bromley and on to Bromley Common (near Hayes) and then take the right fork onto the A233. Follow this for about 2 miles where there is a left turn on a small country road to the village of Downe.

Here in this village at Down House, Charles Darwin (1809-1882) lived and worked for the last 40 years of his life. The house is now a museum and is owned and operated by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Down House

Luxted Road

Downe.

Phone – Farnborough 59119

Opening hours:

Daily 13.00 – 18.00

Closed Monday and Friday, also for the month of February.

Small charge for admission.

It has often been said that Darwin’s work, “The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection”, published in 1859, has had more effect on the way people thing than any other book ever written. Be that as it may, it certainly revolutionized the natural sciences, and biology in particular, and it is interesting to discover what sort of man brought about this revolution.

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury (see under Shrewsbury) in 1809. His father was Robert Waring Darwin, a well-to-do country doctor, and his mother’s maiden name was Susannah Wedgwood, one of the daughters of Josiah Wedgwood, the founder of the famous pottery and china firm. Charles’ mother died when he was only weight, but apart from this he had a happy, though uninspiring childhood. He was no scholar, and because of this was often at odds with his father. However in 1825, at the age of 16, Charles accompanied his elder brother to Edinburgh University to study medicine. This only lasted two years, mainly due to his revulsion at operation performed without anesthetics. He left Edinburgh, and from 1827-1831, he attended Christ’s College, himself for the clergy. However, while at Cambridge, he became a close friend of a brilliant young botany professor, John Stevens Henslow, and it can be said that Henslow altered the course of Darwin’s life by instilling in him a deep interest in botany and natural science. Shortly after Darwin left Cambridge, with a poor degree, Professor Henslow recommended him for the post of naturalist on a naval ship about to undertake a long and difficult voyage. Charles was offered and accepted this position, and from 1831-1836, he sailed around the world in H.M.S. Beagle. The voyage of this ship, and the consequences for Darwin, has recently been told in the magnificent seven part B.B.C. production “The Voyage of Charles Darwin”. If it is possible to see it, we cannot recommend it too strongly. Certainly anyone who has seen it will want to see Downe. This voyage was the most important event in Charles’ life, for it was this that developed him into a mature and critical scientist, and gave rise to all his future theories.

After returning to England (which he never left again) in 1836 he wrote a great deal about his experiences as a naturalist during the voyage, particularly on zoology, botany and geology, and he quickly became known as one of the leading naturalist of his day. In 1839 he married his cousin Emma Wedgwood, and three years later they moved into Down House, where they lived for the rest of their lives. Here on this small estate they raised a family of 10 children (only 7 of whom survived to maturity), and here Darwin, who suffered from chronic ill health, found the peace and solitude he needed to study, to work and to write. It is appropriate to note that the world owes as much to his wife, Emma, as to Darwin himself. For it was she who nursed him for over 40 years and gave him the encouragement, peace and quiet to pursue his work. It is not generally realized that Darwin wrote over 20 books in his lifetime, and over 100 scientific articles. He was a meticulous and thorough worker, to whom time was of little importance in the development of his ideas. In 1837, one year after his return from the voyage of the Beagle, he started a notebook concerning his ideas on “The Transmutation of Species,” which later evolved into “The Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection.” In 1842 and 1844 he wrote out complete sketches of his theories. These manuscripts survive, but they were never published in his day, he was far too cautious. Finally in 1858, while he was work on his book concerning evolution, and after receiving the famous letter from Alfred Russel Wallace (see under Broadstone), he and Wallace had a joint paper on the subject read before the Linnean Society of London. It was entitled “On the Tendency of Species to Form Varieties; and On the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Means of Selection.” The reading, and subsequent publication of this paper, caused little interest, but when in the following year, 1859, “The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection” was published the reaction was quite different. The world was in fact never been the same since, for it transformed not only all of biology and became its central theory, but it also transformed man’s way of thinking and looking at himself, often described as his place in nature. Darwin quickly became world famous, and although a great deal of abuse was showered upon rejected by the old. However they have stood the test of time, and all modern biology is founded on them. Despite his world-wide fame, Darwin died, and despite all the controversy that had surrounded him, so high had his esteem become that he was buried in Westminster Abbey, where the visitor today may see his tombstone.

Down House is preserved much as Darwin left it. The whole ground floor is open to the public (the upper floors are privately occupied) and comprises six rooms, the Hall, the New Study, the Drawing Room, the Charles Darwin Room, the Erasmus Darwin Room and the Old Study. The contents of each room are well marked, explained and beautifully displayed. They contain a wealth of information about the life and work of Charles and his family. Most of the furniture is original, including his desk and chair and his family. Most of the furniture is original, including his desk and chair at which he wrote many of his works, including “The Origin.” The Old Study is much as he would have known it each day as he went in to work, including its spittoon and sitzbath! Some of his personal library is still there. The ground floor of the house is truly a thrilling place, but after it has been seen, the visitor should not neglect to walk down to the bottom of the garden and around the Sand Walk, where Darwin used to walk almost every day, and which he called his “Thinking Path.” Down House is, so to speak, the “Mecca” of biologists, and will not disappoint anyone interested in the history of biology or even the larger of human history in general. Our enthusiasm for Down House was also shared by the Darwin family themselves, for in her “Period Piece,” Mrs. Gwen Raverat , a granddaughter of Charles Darwin, wrote: “For us, everything at Down was perfect. That was axiom. And by us I mean, not only the children, but all the uncles and aunts who belonged there —everything there was different. And better.”

Downe is full of stories about Charles Darwin, and there are other associations which the visitor will hear about, but it is worthwhile mentioning that despite the general hostility of the church and clergy towards Darwin and his theories, there is, on the side of the Church of St.Mary the Virgin, overlooking a sundial and the village square of Downe, the following inscription:

This Sundial is in memory of

Charles Darwin

1809-1882

Who lived and worked in Downe

For 40 years

He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Have lunch at the George and Dragon Pub (where Darwin himself drank his ale) and then walk along Luxted Road to Down House!

The Royal College of Surgeons of England

Lincoln’s Inn Fields

London

Phone – 01-405-3474

Opening Hours:

Normal business hours.

No charge for admission.

Children are not admitted.

Underground-Holborn

The Royal College of Surgeons, which incorporates the Hunterian Museum, was established in its modern form in 1800. It was based then, as now, on the humanitarianism, educational concepts and professionalism which John Hunter (1728-1793) established as the blueprint for medical training, and which became established as the blueprint for medical training, and which became the subsequent pattern followed by medical schools in both Britian and the United States. The major function of the Royal College of Surgeons can be summed up by saying that it is to maintain and improved the standards of surgery in all their varied aspects and it has played an enormous and world wide role in these respects. It is an entirely autonomous body, all of their funds coming from their Fellows and public subscriptions, but none from the government.

It is important to note that the college, including its magnificent Hunterian Museum, is an active working organization, and is not open to the general public. However, it is open to members of scientific societies. Other individuals and groups must make application is neither a natural history museum, nor a museum of medical history. Visitors require some basic knowledge of biology to appreciate it. It is not suitable for children and they are not allowed. Having said all this, we will add that the curator and the porter in charge at the front desk are generally cooperative. But they have responsibilities to the institution they serve, and the public must respect these.

John Hunter (see also under East Kilbride) can figuratively be described as the “Patron-Saint” of the Royal College of Surgeons. Just as his famous brother William Hunter (see under East Kilbride) established obstetrics as a medical science, so also did John put surgery into a scientific category rather than a “butchery procedure” practiced largely by barbers and other untrained people. He eventually became surgeon-extraordinary to King George III and in 1783 established his own medical school in what is now Leicester Square. Here the student had to undergo rigorous training, study animal and human specimens, attend lectures and practical classes, and do research. All the things we now take for granted in medical training. Honors poured in upon him, and over 1000 of his students spread his ideas and methods throughout the modern world. He died 1793 established his own medical school in what is now Leicester Square. Here the student had to undergo rigorous training, study animal and human specimens, attend lectures and practical classes, and do research. All the things we now take for granted in medical training. Honors poured in upon him, and over 1000 of his students spread his ideas and methods throughout the modern world. He died in 1793, probably from syphilis, with which he inoculated himself in order to distinguish it from gonorrhea. Dedication!—but unfortunately the experiment failed into the bargain! He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

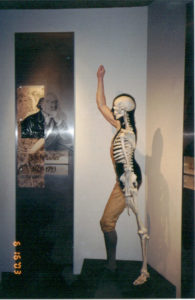

By far the most important exhibit at the Royal College of Surgeons is the Hunterian Museum. Originally, Hunter’s collection comprised about 14,000 specimens, but time, and above all the World War II bombing of the college have reduced the number considerably. Nevertheless, there are still many thousands left and they are magnificently displayed in this lovely and fascinating museum. All the more, remarkable when one realizes that most of it is the work of one man and the specimens are 200 years old! Within the displays are dissections illustrating all the main basic structures and functions of the animal form. These include the endoskeleton, joints, and muscular systems, and nervous systems, organs of special sense, integumentary system, organs of locomotion, the digestive, circulatory, respiratory, excretory, and reproductive systems, as well as ductless glands. One is immediately struck by the incredible skill of the dissections. Guide books to the museum are available, and there are also many other interesting publications on sale. The staff is dedicated, enthusiastic and helpful. All in all, a visit to the Hunterian Museum is a thrilling experience.

The Royal College of Surgeons also has a superb collection of the medical instruments of Joseph Lord Lister (see under Glasgow), many of which are on display in the lobby and can easily be seen. There is also a large statue of John Hunter which dominates the lobby, and there are lovely original portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds and others. The library of the college (which can only be seen by special permission) is one of the great medical libraries of the world, with priceless holdings, including all Hunter’s publications, and most of his case books. Regrettably, his manuscripts are mostly lost.

Finally let us point out that in the central party of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, on the Kingsway side near where Sardinia Street enters, there is a new and lovely mounted bust of John Hunter.

EAST KILBRIDE (Lanarkshire), Scotland

Location-About 400 miles north and slightly west of London, and 10 miles east of Glasgow.

Train-From London (Euston) to Glasgow (Central) and then by taxi or bus to East Kilbride.

Road-There are two main routes from London to Glasgow:

1. Take the M1 north to Leeds, then join the A65 to Skipton and on to entrance 36 to the M6. Go north on the M6 around Carlisle and join the A74 which will join the M74. Take exit 6 which leads along the A74. Take exit 6 which leads along the A74 into Glasgow.

2. Take the Al to Scotch Corner and turn left along the A6 to entrance 40 on the M6. Follow the M6 north and join the A74, which will in turn join the M74. Take exit 6 which leads along the A74 into Glasgow.

To reach East Kilbride from Glasgow by car, take the A749 through Rutherglen to East Kilbride. Upon entering the latter, take the Calderwood turning, where there is a sign pointing to the Hunter Museum on Maxwellton Road.

Hunter Museum (or Hunter House)

Maxwellton Road

East Kilbride

Phone: -East Kilbride 23993 or East Kilbride 41111

Opening hours: There are no regular opening hours, but it is only necessary to phone in advance for an appointment. There is a Hunter Trust w hich administers the museum under the patronage of the Royal College of Surgeons and the University of Glasgow.

hich administers the museum under the patronage of the Royal College of Surgeons and the University of Glasgow.

Small charge for admission.

Seldom have two such brilliant men come from the same family as William. (1718-1783) and John (1728-1793) Hunter, both of whom distinguished themselves as doctors, and left lasting contributions to medicine. Both were born in the little house, now referred to as Hunter House. For an account of John Hunter, see under The Royal College of Surgeons, London, but a brief account of William will be given here.

As a boy, William Hunter attended grammar school in East Kilbride, and at 13, he entered the University of Glasgow where he studied the humanities and the classics. After four years at the university, he was apprenticed as a medical student to a Dr. William Cullen in Hamilton. It is important to realize that in the 18th century, there were still no medical schools as we know them today, and a student of medicine simply picked up as best he could the knowledge of the day, which was not only very little but often wrong as

well. Dr. Cullen had a great influence on William, and as a result of this, he went on to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh, as well as in London and Paris. He was very impressed with the manner in which anatomy was taught in Paris, by dissection, and on returning to London in 1746, he set up his own anatomy school which was, for its day, of such high quality and so successful that it lasted until his death in 1783. As part of his

school, he set up one of the first anatomy museums in the world so that students could study the specimens, both normal and pathological on a year-round basis. In London, William went from medical honor to medical honor, and finally became obstetrician to the Queen, whom he attended during her first pregnancy in 1762, and it was in obstetrics that he made his greatest and lasting contributions. Prior to this time, obstetrics was based on a vast array of ignorance and superstition and was in the hands of quacks and untrained midwives. Hunter led the way in putting it on a scientific basis.

In 1774, after 25 years of study and collecting scientific information, he published his classic work “The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus”. It was by far the best book on the pregnant uterus every published, and with it, obstetrics as a science was ushered in. It contained 24 magnificent engravings of the pregnant uterus by the artist Jan van Rymsdyck, and was dedicated to the King (George III). The original copy of this with text

both in Latin and English, together with the hand-done illustrations of the artist are housed in the Special Collections Department of the main library of the University of Glasgow on University Avenue. It may be seen by permission of the librarian, and it is worth the effort!

During his lifetime, and in addition to his museum specimens, William amassed valuable and extensive collections of books, pictures and coins, all of which he left to the University of Glasgow, where they can be seen today (see under Glasgow), and are very impressive. He died in London in 1783, but medicine, and obstetrics in particular, owes an eternal debt of gratitude to William Hunter.

On the outside of the Hunter House is a plaque which reads as follows:

The Birthplace of Two Great Scotsmen

William Hunter and John Hunter

Born 23 May 1718 Born 13 Feb 1728

Died 30 March 1783 Died 26 Oct 1793

Pre-eminent in Medicine and in Surgery.

The house, including the barn and garden, is much as it was in the Hunters’ day and has been nicely preserved, despite a modern development all around it. On the ground floor is a one room museum, with a wealth of interesting Hunterian material as well as various items of medial interest from the 18th century. The visitor can also see, by request, the tiny first floor room where both William and John Hunter were born. Hunter House is in a somewhat out of the way place, but the effort of going to see the birthplace of these two great Scotsmen is well worth it.

EAST WELLOW (Hampshire)

Location-85 miles southwest of London, near Romsey.

Train-London (Waterloo) to Romsey, and then by taxi.

Road-Take the M3 or A30 from London to beyond Basingstoke and join the A33 around Winchester. Then fork right along the A32 to Romsey. At Romsey, take the A27 towards Salisbury, but after about 2 miles, turn left to “The Wellows” and follow signs to East Wellow.

Church of St. Margaret of Antioch

East Wellow

Hampshire

It is in this churchyard that Florence Nightingale (see under St. Thomas’ Hospital, London) is buried. One might have imagined that so great a benefactor of mankind as Florence Nightingale, would have been buried in Westminster Abbey, but during her long life, she always spurned publicity and honors, and was no different in death. She is buried in a common grave alongside other members of her family. The grave is easily found, being only a few yards from the main entrance to the church, and has a prominent spire

above the tombstone with inscriptions on it of the family buried there. Florence Nightingale is inscribed simply as F.N. with her birth and death dates. Inside the church is a plaque dedicated to her, and on the porch is one of her famous lamps, which here family gave to the church. The reason Florence Nightingale is buried at East Wellow, is that nearby, her family owned a large house, Embley Park. It is now a school (Embley Park School), but the outside of the main building is much the same as in the 19th century, and still in the beautiful setting that Florence Nightingale knew. It is located on the south side of the A27, between The Wellows sign and where the road joins A31 near Romsey. The house is clearly marked at the main gate. There is no harm in driving in to see the exterior and its setting, hut the building itself is private.

EDINBURGH (Lothian), Scotland

Location-375 mites north of London

Train-From London (King’s Cross) to Edinburgh (Waverly). From Glasgow (Queens) to Edinburgh (Waverly). Road-Take the M1 or Al to Scotch Corner, and then fork right to Durham and Newcastle. At Newcastle, join the A696 to Ponteland, and at Otterburn, this joins the A68 to Dalkeith and Edinburgh.

Edinburgh is one of the most ancient and beautiful cities in Britain, which in addition to many cultural and political aspects, has a famous scientific history centered in its great university. During the 18th and 19th centuries, it had one of the most distinguished medical schools in the world.

Sir James Young Simpson Museum

52 Queen Street

Edinburgh

Opening hours: Normal business hours. The museum is maintained by the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, but the house is used as a shelter by the Church of Scotland.

No charge for admission.

Sir James Young Simpson has a permanent place in the history of medicine, not only for his great contributions to obstetrics, but above all for his discovery in 1847 of the anesthetic properties of chloroform. This became the worldwide standard anesthetic for nearly 100 years, and has only been generally superseded in very recent times. Simpson was born at Bathgate, the son of a baker, David Simpson. It is said that his mother, who died tragically when be was only nine, decided very early on that young James should be the scholar of the family. He did not disappoint her! While in his early teens, he attended arts classes in Edinburgh, but very soon switched to medicine, and at the early age of 19, became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. Soon after he was practicing medicine in Edinburgh, with a specialty of obstetrics at which he spend most of his life. It is of great interest that Charles Darwin and James Young Simpson were both medical students at Edinburgh at the same time. However, it is of even greater interest that they were both revolted by operations performed without anesthetics. Because of this, Darwin gave up medicine and went on to other things, but fortunately, Simpson decided to try to do something about it. It is worthwhile recording in this respect the actual operation which had such an influence on Simpson, because it will help the modern reader to understand how surgery has changed over the past 150 years. The operation was an amputation of the breast of a woman, and was performed by Rob ert Liston, one of the most famous surgeons of his day. The normal procedure for this was simply to lift up the soft tissue of the breast with an instrument resembling a hook, thus enabling the surgeon to sweep around the mass with his knife, hopefully in two clean cuts! Simpson, like other medical students (all males in those days), had seen other operations and was keen to see this one. However, as Liston picked up his knife, Simpson observed the horrified look of terror on the woman’s face and turned away leaving the room. In those days, one of the major attributes of a surgeon was the speed of which he could perform the operation. Operations had to be performed in a matter of seconds, rather than minutes, otherwise the patient would almost certainly die of shock. Liston was a master of the art, of whom Simpson himself remarked that “‘he amputated with such speed that the sound of sawing seemed to succeed immediately the first flash of the knife”.

ert Liston, one of the most famous surgeons of his day. The normal procedure for this was simply to lift up the soft tissue of the breast with an instrument resembling a hook, thus enabling the surgeon to sweep around the mass with his knife, hopefully in two clean cuts! Simpson, like other medical students (all males in those days), had seen other operations and was keen to see this one. However, as Liston picked up his knife, Simpson observed the horrified look of terror on the woman’s face and turned away leaving the room. In those days, one of the major attributes of a surgeon was the speed of which he could perform the operation. Operations had to be performed in a matter of seconds, rather than minutes, otherwise the patient would almost certainly die of shock. Liston was a master of the art, of whom Simpson himself remarked that “‘he amputated with such speed that the sound of sawing seemed to succeed immediately the first flash of the knife”.

From that moment onward, Simpson determined to try to do something to relieve the pain suffered in operations and since he specialized in obstetrics, he also quickly became concerned to try to relieve the pain suffered by women in childbirth. Doctors at that time had to be somewhat indifferent to the pain suffered by their patients for they could do nothing about it, but Simpson set himself the task of trying to reverse this, and was indeed successful beyond his wildest hopes. In the first half of the 19th century, mesmerism was popular as a pain reliever. Simpson tried this in 1837, and also other methods as they became available but all were very unsatisfactory.

In 1845, there were no safe or reliable methods of testing new drugs, but Simpson and his two assistants, Dr. George Keith and Dr. Matthew Duncan, undertook to test a whole variety of available drugs on themselves. Their method was simple, almost to the point of absurdity! After dinner at night, Simpson and his two assistants sat around the dining table, poured out a sample of a drug into a saucer, and proceed to smell it and describe its effects. They had same horrible experiences, needless to say, and on more than one occasion, Simpson nearly died from the effects of the drugs. However, they pressed on their quest, and after dinner on the 4th of November 1847, they all inhaled a sample of chloroform. Very rapidly they became unconscious and slipped under the table. Upon recovery, Simpson knew at once that he had discovered something important and hoped it would be the answer to his search. Within a week, he lectured on it at the university, within two weeks, it was used in an operation at the Royal Infirmary, and within a month, Simpson had used it on his female patients in childbirth. It must be pointed out that this was not really the first operation at which an anesthetic was used. The credit for this is usually given to the two American dentists Morton and Wells (see under Boston and Washington, U.S.A.) who used ether and nitrous oxide. As a result of their discovery (just prior to the discovery of chloroform)

Simpson also tried either in childbirth, but it proved dangerous and very unsatisfactory, while chloroform was quite the reverse, and proved to be very reliable One might have thought that Simpson would immediately have been hailed as a great human benefactor, but that was not the case. Many surgeons opposed the use of chloroform in operations, because they thought that the pain suffered during these was good for the patient’s character and “moral fibre”! However, it was for its use in childbirth that the worse abuse was hurled at Simpson Was he not flying in the face of Providence?- -for did not the Bible decree”- – in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children;-“ (Genesis ~:16). Needless to say, there were those (mostly men) who believed passionately that the pain of childbirth were also good for the woman’s character! Fortunately, Simpson himself was a devout Christian, and he patiently but firmly answered abuse by the critics, and the opposition gradually faded. The final “seal of approval” was given in 1853 when no less a person than (Queen Victoria (the titular head of the Church of England) accepted chloroform at the birth of her eighth child. In so doing, she did all women a great service.

The use of chloroform quickly spread around the world, a new era of surgery was ushered in, because speed was no longer a criterion, and women were relieved of the worst pangs of childbirth. But more than this, Simpson’s discovery and humanitarian attitude as an obstetrician, raised the status of women above that of some kind of “second class” human being. Unfortunately, Simpson’s fight is still not completely won. For his services to humanity, James Young Simpson was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1866 and when he died in 1870, the city of Edinburgh gave him a funeral the likes of which the city had never seen before nor since. It was hoped by many that he would be buried in Westminster Abbey, but his widow, remaining true to the nature of her husband as a simple man, declined the offer.

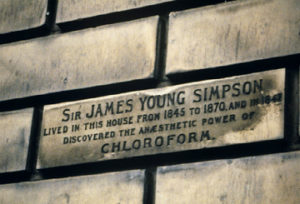

At 52, Queen Street in Edinburgh stands the house where Simpson lied for the last 25 years or his life, and where also he died in 1870. In his day, it was much more than a family residence. Here he and his assistants dealt with a constant stream of patients, and bedrooms were provided for those who came from a distance. There was also a constant influx or visitors, including medical men seeking advice. The outside of the house is marked with a plaque which reads as follows:

Sir James Young Simpson

lived in this house from1845 to 1870

and in 1847 discovered

the anesthetic power of

CHLOROFORM .

Most of the inside of the house is generally unaltered, but is now used for the purposes of the Church of Scotland. However, on the ground floor is Simpson’s dining room, in which the anesthetic properties of chloroform were discovered. It survives intact and is known as “The Discovery Room”. You can ask permission of the person on duty for the Church of Scotland to see the room, and they will also give you a pamphlet on the life of Simpson.

To us this room is an absolute gem in human and medical history, and still remains much as Simpson and his family would have known it. His huge dining table is still there, together with the cabinets and other furniture that he used while testing the drugs. On the mantle piece are his wood foetal stethoscopes, his crucifix which he used as a knife, his pill box, Lady Simpson’s bible, and his brandy decanter, into which he poured the chloroform on the evening of November 4, 1847. This can only be described as “true dedication”! In addition to this memorial to Simpson, the city of Edinburgh has erected a fine statue of him. It is considerably larger than life, and is located on the south side of Princes Street near the corner of South Charlotte Street. He is always depicted smiling, and this surely has some meaning!

University of Edinburgh

Old College South Bridge

Edinburgh

Opening hours: Normal business hours.

No charge for admission.

The origins of the University of Edinburgh go back beyond 1583, but in that year, the first students in Arts and Divinity were formally enrolled and from that time onwards, it has had a distinguished history, particularly in medicine in the 19th century. Joseph Lister (see under Glasgow) was in Edinburgh both before and after his stay in Glasgow (1860-1869), which was where be did his monumental work on antiseptic therapy. He was in Edinburgh from 1854-1860 as a young assistant to a famous surgeon of his day, James Syme, and returned to Edinburgh again in 1869 as Regius Professor of Clinical Surgery at the university, remaining there until 1877. The house in which he lived during this time is a 9 Charlotte Square (north side) and is marked by a plaque, but it is privately owned. Lister always felt it was the University of Edinburgh that gave him his start in a distinguished medical career, and in gratitude he left all his many honors to the University at Edinburgh. These are located within the Quad of the Old College and are

displayed in a large case at the head of the main staircase leading to a beautiful Library Hall. They can be seen with the permission of the Bedellus of the university. It is a truly remarkable display, and gives some indication of the esteem in which Lister was held in his day, as well as what we of later generations owe to him. Above the case is a portrait of Lister by J.H. Lorirner. The Library Hall (built 1827) should also be seen, with its array of busts of all the famous professors of the university, as well as such interesting things as the library table of Sir Waiter Scott, and Napoleon’s table from his study on the Island of St. Helena. There are a host of other historical associations of the University of Edinburgh, and it was here that Charles Darwin (see under Downe) and his elder brother Erasmus attended medical school. In fact, they both lived just around the corner from the Old College at 11 Lothian Street. Their house is now unfortunately completely gone, a victim of redevelopment.

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

Lauriston Place

Edinburgh

Opening hours: Normal business hours.

No charge for admission.

This is the modern Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, which is a huge complex of

hospitals, dating from 1870. In addition to his professorship at the university, Lister had an appointment here during his second stay in Edinburgh, and he lectured in the so-called Lister Theatre. Also as part of the Royal Infirmary, is a James Young Simpson Maternity Wing, and inside the main rotunda is a large and striking portrait of Simpson by Norman Macbeth.

The Old Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and Surgeons Hall

12 High School Wynd (corner of Infirmary Street)

Edinburgh

Opening hours: Normal business hours.

No charge for admission.

These two buildings were originally a high school, then became the surgical hospital of the Royal Infirmary, and are now the Geography Department of the university. Both Lister and Syme worked here in the surgical wards and extended the use of antiseptic therapy which Lister had developed earlier in Glasgow. The interiors of these buildings have been much altered since Lister’s day but the exteriors are almost the same. It is a tragedy that the fine old lecture theater that Lister used has been altered almost beyond recognition. The fact that Lister and Syme both worked here is commemorated by a nice plaque at the front entrance which reads as follows:

James Syme (1833-1869)

and

Joseph Lister (1869-1877)

While Regius Professors of Clinical

Surgery in the University of Edinburgh

had charge of the wards in this building

then the Old Surgical Hospital

and part of

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

Erected by Surgeons of Toronto-Canada 1957.

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

Nicholson Street

Edinburgh

Opening hours: Normal business hours.

No charge for admission.

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh is the Scottish counterpart of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, and is primarily responsible for the maintenance and improvement of the standards of surgery in Scotland. In this regard, the college has played a long and distinguished role in surgical history. Both Lister and Syme, as well as Simpson, were Fellows of the college. Like most of these colleges, it is large and imposing both outside and in, and has a fine collection of portraits of its distinguished Fellows.

There is a very valuable and extensive medical library going back five centuries. The library also has a small number of Lister’ s letters, notes, testimonials etc., but a much larger collection of materials relating to the work of Simpson, which includes many letters and other correspondence referring to anesthesia as well as his lecture notes. The library is not open to the public, but permission to see it may be requested. One may also ask to